des'esparon series whose history

Paper 15 given by ROBERT GRACE

@ III. International History Conference

HISTORY’16 DAKAM, Eastern Mediterranean Academic Research Center, Istanbul, Turkey –

May 6 -7, 2016 ISBN 978-605920723-2

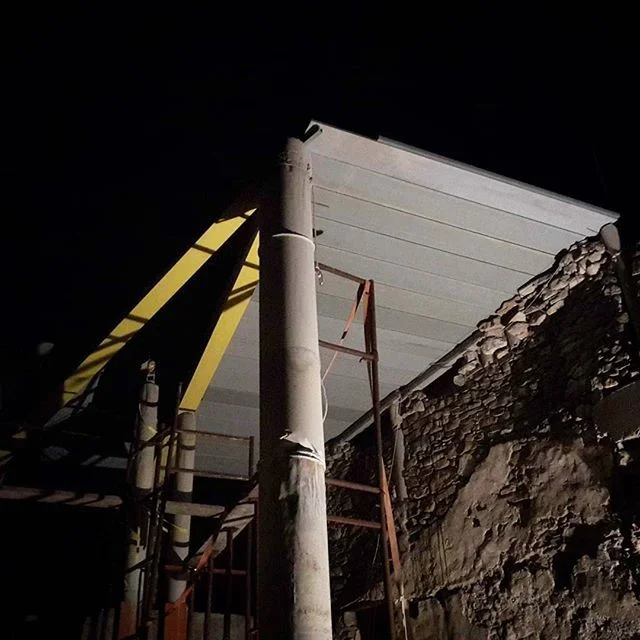

I have been building our house in the South of France for the past 11 years, last year with my son we completed the roof structure. Soon after we were subjected to a concerted effort from the inhabitants of the village (five adults) to expressing displeasure of the scale/height and glass of my project, despite the superstructure having been in place for five years. Their complaints to; myself, my son and the local mayor; is the genesis of this paper.

In those “discussions”, the terms used and concepts expressed; evidenced thinking, readings and received wisdoms that echoed in my mind.

Years ago I started a PhD which was to be a lexicon of urban planning terminology, a comparative study of the same notions in different cultures, languages and cities. It wasn’t long until my suspicions were vindicated; this terminology, of urban planning bureaucrats as objective and sacrosanct. Were indeed completely subjective. My researches were an effort to debunk the premises upon which urban planning is practised. This paper uses the same etymological analytical tool, on the terms my neighbours slung around with fervour in the objectivity of their tropes.

The Method produces a speculative presentation of my disparate thoughts generated in an effort to locate and explain this highly specific and personal experience.

Architecture is intrinsically political, through its relation to economic and political frameworks, and specifically to its processes of production but also too its form.

How Architecture is formally read relies on tactile qualities, configurations of space and functional relationships as much as in the figurative: its cultural capital can be slow to build up.

Any reading of architecture (as for other creative works) is inured in its historical moment and in its social context.

Production and formal reception of architecture are its two political dimensions although they are not unrelated; these roles may and often do act independently at differing times and on different constituencies.

Modern, Modernism----

The Modern Movement emerged over 100 years old, its deepest concern was with the new industrial techniques of production and standardisation, using housing as its social programme attempting to redefine the socio economic role of architecture. It was the Avant Garde, the brave new, and was adopted for its potential to engender social change; it was anti conservative, eschewing historical reference and sourcing industrial production for its methods and imagery, driven by the multiple technological possibilities.

But by the 1960’s Critics - Architectural and Social, saw the revolutionary zeal of the modern movement as unfulfilled. For these critics Modernism had evolved into a destructive and alienating architecture, that had in the post war period it had become routinized corporate tool, American (new world) rather than European. Playing into the hands of what became known as post-modernism, with even modernism’s supporters (from the traditional left), seeing the demise of social engagement as an abdication of the architect’s responsibility. They cited the split between architectural form and social institutions as the scourge of, capital; that through alienation of the public had denied the fostering of urban communities.

Postmodernism or postmodernist historicism (take the decade 1977 – 87) allowed for the rediscovery of history which had been denied in the hermeticism of modernism; with its messianic faith in the new and obliteration of the past; wiping out traditional difference and experience. PM railed against the utopianism of modernism and its universal rationalism that limited diversity and complexity. History was seen as more communicative, recognisable and able to provide architecture the means by which to re-establish its public role. This renewal of history generated from egalitarianism of the 1960’s social critique, however its assumptions being mostly social integration and preservation, not social change. In differing strains of historicist postmodernism, according to the political bents of its practitioners, on one hand to re-establish the continuity of culture and to renew a sense of community; via a nostalgia for a 19th Century eclecticism positing a moral equation of style and social function. And on the other the aesthetic aspect of history (style) co-opting the picturesque of the 18th Century to promise freedom and change to enable the representation of varied experiences, allusions and moods; history was the resource for diverse, varied and complex visions of the present.

If stylistic eclecticism meant aesthetic freedom it was by means of technological progress with no one mandated style, it made many styles and the past offered up an infinite field of possibilities. In fact this propulsion towards art for art’s sake was no different, to the same cult at the beginning of the Roman Empire (Reigl). However a sort of anything goes appropriation became the norm by the middle of the 80’s, just as the heralds of celebrity culture were seen in the emergence of the starchitects in the glossies as product endorsers, style makers and purveyors of lifestyle.

Postmodernism at its best subverted and parodied convention, spotlighting the paradoxes and the fleeting nature of a historic moments. It challenged modernism and its contradictions throwing tradition up against innovation, the figurative versus the abstract and fragmentation countered order. Then it slipped, historical allusion adopted nostalgia, the superficial and simulacra before plunging into pure revival and mannerist quotations. The promise of revisiting history was freedom and a chance to recoup lost values, the downside was the realisation that perhaps the present was not any better than what had gone before and acceptance of the arbitrariness of aesthetic and political choices.

The possibility of many pasts and many styles had transformed into a single style and a single past. The power of allusion was irresistible it promoted Postmodernism to overwhelming adoption by the market, and had become a historical style on its own.

Contexualism

I capitulate that its greatest legacy (postmodernism (historicist) was the movement against the homogenising and alienating aspects of modernism’s large scale urban renewal. This reassessment led to Contexualism, and this is at the heart of the issue of this presentation, it led to the meteoric rise of preservation. Alois Riegl (writing at the dawn of the 20th C) and more recently Françoise Choay on monumentalisation and museumification revealed the problematic nature of contextualism as resistant rather than regenerative, it attempts to maintain a perceived status quo that has rarely transformed community life.

Contextualism, provided a great support to gentrification and in no small way contributed to the erosion of neighbourhoods and creating a new hegemony of uniformity. To copy what is there negates history itself. It had de-generated into a spent nostalgia.

Edouard François: Collage Urbain , C H AMP I G N Y - S U R -MA R N E - F R A N C E, 2012 unmediated contextualism

Village context

My project is one of the few in the village in recent years to have obtained a building permit, the remoteness and general ambivalence masquerading as good neighbourliness has allowed via the attrition of small multiple illegal/unregulated/ uncontrolled additions and transformations to slowly change the visual and aesthetic nature of the village. So when accused of denaturé the village by my neighbours they display either very poor memory or selective amnesia. One of the most photographed houses in the village (in tourist publicity) as the epitome of traditional architectural treatment is in fact one that has been completely remodelled and altered in the 1960’s especially its form and details, in fact its stuccoed exterior covering up industrialised masonry and not the local stone. Concrete and concrete block remain the material of choice in contemporary “traditional” construction. The 11th century chapel has been coated in an industrialised render and roofed in slate that derives its selection as a material and curved detailing from a regional style some 60kms away, whereas the local tradition is square edged limestone (lauzes). The newly built communal bread oven (four a pain) at best guess approximates the edifice that might have been there, it was built using a laudable local scheme by apprentices working with a master mason. It was inaugurated by the local historical association all in (19th C) dress.

Four au pain, Esparon

2009

circa 1950

inaugurated 2015

It gives weight to my developing theory that we only like old buildings when they are new. Authenticity clearly in terms of perception, readings and representations is a movable feast, completely subjective. Evidently the village has changed and will continue to change however my neighbours’ myopia forces them to see difference as a challenge to their overarching perception of a

homogenous village of indistinguishable parts, it is in fact a heterogenous agglomeration of very different pieces. In an evolving community contextual mutations are inevitable; any new project will challenge and change both the visual habits and the elements that contextualized the project in the first place. The will to preservation flirts with the concept of homogeneity where the best they could hope for is a controlled heterogeneity. Heterogeneity will accommodate difference.

Riegl’s study pointed to the conflicting relationship between the legacy of the past and current values. Central to him was time’s destructive force and the subsequent mortality of culture itself. Its constant demise highlighted by the resurgence of the new and lapses into the old, leaving a wreckage rather than a museum of achievements. Historicist regurgitations, throw up a past that never was and require the present to bow before what is an empty throne. He claimed all aesthetic values were contingent on history, he recognised that contemporary concerns, deeply effect our perceptions of the past: over time there is no objective past, only a constantly refracting absence in the memory of the present. (The Modern Cult of Monuments: Its Character and Its Origin, Alois Riegl, Translated by Kurt W. Forster and Diane Ghirardo, Oppositions 25, Monument /Memory Edited by Kurt W. Forster, Fall 1982 for IAUS, Rizzoli New York. Translated from, Gessammelte Aufsatze, Alois Riegl, Augburg-Vienna: Dr. Benno Filser, 1928).

Nimby, not in my backyard

We like modern but not here…… the technological development of insulating glass, allows for increasingly larger panes of glass to be used. The history of architecture could be treated as a history of technological development. For my neighbours glass is the ogre, large expanses are for them alien/they read alienation, they read difference, they read lack of respect of their patrimony / heritage, they aspire to historic preservation classification & traditional materials (the haptic) and techniques(artisanale), they deny jealousy, they are suspicious of apparent administrative arbitrariness and of the architect playing the system, they are :- wary of class distinction, full of prejudice, proud of their life style; their view of the future is a restoration of the past, because imagining the future is too hard or beyond their capacities (a role for the architect?), they dream of sustainability, they….respect the status quo, they deny they have changed the village through attrition, they are unsure of individual rights / sovereignty and what that may bring, they are exorcising frustration and anger. They do not want what is not of that place.

Neighbours

My neighbours number four households, permanent residents of the village with one of them living across the small valley. In fact two of these households are shared. There are five adults and two children (teenagers). Further across the local valley a small farm, one of these farmers is the brother of the last/late native of the village, their parents and grandparents are buried in the cemetery. Have little to do with the village other than shoo their cattle across the access roads to terraced pasture to avail them of the overflow from the small spring fed reservoir. In summer the evening air is often filled with the sounds of the ten cowbells. These neighbours are not from the village nor are they familial remnants of natives (their tenure in the village ranges from 6 to 40 years). They are all from elsewhere, all are immigrants and not in rural employ: the high school maths teacher, the retired advertising agency graphic artist whose sideline is honey producer, the publishing company director; (all from Paris) the Physics lecturer (a town 40 kms away) and the public theatrical arts organizer with a recent Phd (central France). Save for the occasional honey maker they all work elsewhere, the village is for them a dortoir / dormitory a new world for them, a place where they chose to live, theirs is a modern existence of the ease of choice. A choice not of necessity but for lifestyle / pleasure reasons, the sign of a rich society. Not a squeak out of the holiday home owners.

Classification The village is classified in the national register as a site pittoresque, the images shows why, it is thus subject to control by the Architecte de Batiment de France. The locals think this registration relates to the architecture of the village itself, this is not the case. However there is confusion in the application of the developmental controls this affords the authority. There are no guidelines for the control of building in such a zone, so the control reverts to batiment classée / or preservation zone. This default position is confusing however as an architect, and a Parisian architect as well, there is a local inferiority perception that we can get anything through. Further through the vagaries of the French building permit system what happens inside your walls i.e. Not on the boundary is not controlled, even if can be seen from the outside, as long it is within height limitations.

Case study Esparon

Beyond the fact it is a new house not a rehabilitation, within the remaining old walls it is a palimpsest built of many of the materials that had existed as another house transformed and repurposed. In the traditions of modernism it is an abstraction; Formally & Materially not of that place and of that place at the same time. It is historicist in that it clings or reattaches as does its creator to a sense of the avant-garde/ better world/revolutionary/romantic ardour of the modernist dream. This is achieved by developing new techniques whilst bastardising interpretations of old ones thus procuring a dissenting architectural message; given financial and resource constraints; via changes in the construction processes & developing a new building type of a radically different scale/scope/amplitude. By clinging to a new world view as an outsider it has permitted an anarchistic approach to neighbourly relations. I am not trying to make something to fit in, to be polite or deferent in the context as found. Resolutely remaining wholly responsible for improving its (the building’s) situation

Coexistence of difference

Agree to Disagree! This could describe my life as an architect, in our village it is not like mindedness but a series of divergences that makes up the community. It is abundantly clear that cultural & political dimensions of all interpretations and presentations of history are deeply nuanced. The description of the Village Medieval d’Esparon in online advertisements for rental of their various houses belies my neighbours’ personal aspirations / values and like the complaint of my project, is circumscribed by what they may see, what they want to see: Where any view of the future is predicated by particular subjective views of the past, of their view of others, of how others perceive them and most importantly their view/s of themselves.